The first folio’s publication in 1623, 8 years after Shakespeare’s death, brought us 18 plays from Shakespeare never published during his lifetime — about half of his canon. Among them is The Taming of the Shrew, probably Shakespeare’s first comedy. For a prolific writer, Shakespeare cared very little for the publishing of his plays, censorship laws made it difficult for any Catholic to publish, even a great playwright like Shakespeare would find difficultly in publishing. Instead, the prolific playwright dedicated himself to staging stories in the theater, like The Taming of the Shrew, where an actor tells the audience in the introductory scenes that these plays are “a kind of history.”

His first comedy uses his well-known play-within-a-play motif (famous in later productions like Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hamlet). But this play is a curious kind of history, for it starts off with a set-up scene where a practical joke is played on Christopher Sly (‘cunning Christ-bearer’). He wakes from his drunken stupor to find himself declared a Lord who can’t remember the last 15 years. And part of the joke is that as he wakes he is forced to watch this play, which is, as mentioned, “a kind of history.”

Only, for the Catholic audience, this kind of history reveals reality. We’re quickly transported to Padua, a kind of England. In Padua, the father of a prominent house is Baptista, who has 2 daughters of marriageable age — the elder Catherine, who none wish to court, and the younger Bianca, who all wish to court.

To hear Shakespeare and interpret this Catholic allegory, a few things to note. Baptism is the only sacrament common to both Catholics and Anglicans, so this is a very astute name choice from Shakespeare to help disguise and yet unlock the allegory of the two main churches in England. Next, the elder daughter, is named after Catherine of Aragon, the Catholic Queen discarded by Henry VIII when he created his State church and wedded his new wife under Anglican rites. The name means “pure.” In the story, the older sister and noted shrew, Catherine, represents the Catholic church, the old faith that none in Padua desired to wed. Curst Cate would have been a common refrain lamenting the displaced Queen, and in this story is symbolic of the displaced Church.

None woo Catherine until Petruchio comes to town ready to “wive and thrive.” And once again, for a Catholic audience member, his name sounds a lot like Peter, the office of Peter being the vicar of Christ and head of the Catholic church on earth. This allegory is confirmed for Catholics when Petruchio officially introduces himself to the audience,

“Thus it stands with me: Antonio my father is deceased, and I have thrust myself into this maze, haply to wive and thrive, best as I may. Crowns in my purse I have, and goods at home, and so am come abroad to see the world.”

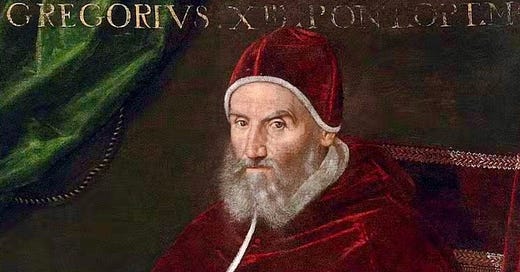

A couple key historical items to note. Antonio is the given name of Pope Saint Pius V, the saintly pope who excommunicates Queen Elizabeth in 1570. And Pope Gregory XIII is the pope who follows (his papacy was from 1572-1585), the one whom Petruchio specifically represents in the play, going to woo the curst bride of Christ.

There are two things, possibly above all others, that Pope Gregory XIII would be known for among the English people of Shakespeare’s time. One, the Jesuit mission to England which began in 1580. And two, the Gregorian calendar of 1582, which better aligned our solar calendar with the seasons.

Both these items are represented in the play.

The Jesuit mission is represented in all the disguises that the travelers to Padua, except Petruchio, must don to woo Bianca. As it was illegal and punishable unto death to be a Catholic priest in Elizabeth’s England, the Jesuit mission meant the English priests took on disguises to woo Anglicans back to the pure faith as well as bring the divine sacraments to Catholics who had kept the faith despite torment and torture.

The calendar is mentioned as a joke during an interchange with Petruchio and his new bride Catherine. The historical allusion is that when Pope Gregory announced the new calendar in 1582, Europe was then divided in telling time by religious lines. Many Catholic countries adopted the new calendar immediately, skipping ahead 11 days from October 4 to October 15 overnight. While the slowest Catholic countries adopted the new calendar within 2 years. Instead, the Protestant countries would take centuries to align. (The American colonies wouldn’t adopt the calendar till the mid-18th century). And so it’s a part of hilarious Catholic comedy that Petruchio dictates the time to his shrewish wife who while disbelieving learns to believe her husband and calls it as he sees it,

“Then God be blessed it is the blessed sun

But sun it is not, when you say it is not,

And the moon changes even as your mind.

What you will have it named, even that it is,

And so it shall be so for Katherine.”

It’s a bit of irony at the “shrewish” Catholics aligned with the Pope almost immediately, while the Protestants took centuries to heed his wisdom. Another moral to explore for another time.

There is so much more to comment on this play, an amazing Catholic comedy, but then this summary wouldn’t be considered brief. And so, for the sake of brevity, we once again urge one another to hear Shakespeare, and in doing so love the bride of Christ even more every day called ‘today.’

“Blessed are your eyes because they see, your ears because they hear! In truth I tell you, many prophets and upright people longed to see what you see, and never saw it; to hear what you hear, and never heard it.” — Jesus of Nazareth, King of Kings

Pope Gregory XIII, an oil portrait by Lavinia Fontana

Bravo! Amazing and delightful.